I meant to post a few things before this, but the holidays and work and an obnoxious on-and-off illness have interfered. Still, it's time for a bit of partying!

On the 21st of December I attended a workshop called "Science is Murder," sponsored by the Washington Academy of Sciences. Authors Louis Bayard, Dana Cameron, Ellen Crosby, and Lawrence Goldstone all discussed how they handled the scientific content of their books. It was a very interesting evening and I got autographed books from all four, that I'll be reviewing in coming months.

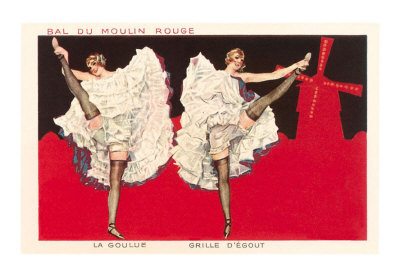

I'm going out tonight, with two of my best friends, for dinner and then a burlesque show at the Red Palace, and it should be a lovely time. Since I allowed myself to daydream about the Phantom Ball (a pipe-dream about a Halloween dance party), I've found myself wondering about a New Year's Eve edition, only going for a different feel...a Belle Epoque, Parisian, Folies Bergere/Moulin Rouge sort of show, with a lavish buffet, champagne flowing like water, an orchestra and a program of cabaret songs and selections from Offenbach and Lehar and Strauss and Romberg and whoever else (no Gilbert & Sullivan, I am horribly sick of Gilbert & Sullivan), and a line of cancan girls at midnight. Kinda like this clip, from a production of Lehar's "The Merry Widow" in Geneva.

I've lately decided that the world needs more operetta, and not just G&S. Offenbach had a bit a revival lately with productions of "Orpheus in the Underworld" all over the place, and hopefully we can revive his other operettas as well. The French operettas are naughty (Offenbach's were often glorified peep shows), and Viennese operettas dealt openly with infidelity and sexual intrigues, and all had wonderful music and lovely waltzes. While they may not have the wordplay of G&S, their subject matter often makes G&S operettas seem overly cutesy and twee, and sadly dated where their French and Viennese cousins have aged much more gracefully. (Offenbach's "Orpheus" translates beautifully to modern times, with its theme of an unhappy marriage being enforced by the personification of Public Opinion, these days often played as a TV news crew. I'll freely admit that G&S's "Iolanthe" has political satire that's still relevant, and probably always will be, but others, like "Patience" and "Princess Ida," are more valued for their music and wordplay rather than the relevance of their spoofery.)

So here's my cry for 2011...BRING BACK THE OPERETTA!

And have a wonderful and safe New Year's Eve, Dear Readers, and I'll see you in 2011.

Friday, December 31, 2010

Monday, December 20, 2010

Joseph Shearing's AIRING IN A CLOSED CARRIAGE and the Florence Maybrick Mystery

Joseph Shearing was one of the many noms de plume adopted by Gabrielle Margaret Vere Long, (seen above) who is probably best remembered today for her work as Marjorie Bowen. But as Joseph Shearing, she wrote a series of mystery/thrillers based on true murder cases that were well-regarded in their day and are ripe for rediscovery.

AIRING IN A CLOSED CARRIAGE (1943) is the story of young May Beale, the Virginia-born daughter of a cotton-growing dynasty, and of her marriage to wealthy John Tyler, a cotton broker of Manchester, in the 1880s. May's marriage is a disaster; a well-bred and well-educated woman, she's out of place in working-class Manchester and in the house of her culturally-challenged parvenu husband. John doses himself freely with patent medicines and is an arsenic-eater; he also keeps a mistress on the side and has fathered numerous children on her, as well as a number of other conquests. May is pursued by a local roue, and is also the lust-object of John's vicious brother Richard, who seeks to destroy John's home and claim May for himself.

Of course, it all goes haywire; John becomes deathly ill, and eventually dies. Was it his patent medicines or did May poison him with the arsenic? Richard, jealous when she's suspected of an affair with the local stud, does his best to frame her for murder, and plays up the fact that May had begun to seek a divorce. May stands trial and is convicted to hang, but her sentence is commuted to twenty years' imprisonment because it can't be proven if the arsenic she supposedly administered truly did the deed, or if it was the arsenic already in his system. In the epilogue, she passes away, old and lonely and forgotten, rejected by her children, reflecting that her life was like an "airing in a closed carriage" (an instruction to the sequestered jury in her case), of always being boxed in and imprisoned, never truly her own person.

It kinda sounds like a soap opera, and it is a bit leisurely in its pacing, but I liked it a lot. The first section, "Schoolgirl's Posy," introduces May and her suitors, and plays up their vulgarity and her naive delicacy. Chapter two, "Lady's Posy," introduces May as Mrs. Tyler, struggling in her increasingly unhappy marriage, with children who are kept from her and servants who spy on her as much as they serve her. "Invalid's Posy," the third chapter, is the longest, and may seem slow-moving until you realize that the chess pieces are being moved and things are being arranged, as the Tyler marriage deteriorates and implodes, May looks into a divorce, and John is suddenly taken ill. "Prisoner's Posy" covers the arrest and trial, and "What Was Left in the Chocolate Box" briefly looks at her prison years. And then the sad epilogue.

There's more than meets the eye, too. Some might be a bit snobbish; Shearing has no sympathy for the nouveau riche Tylers, aping the style of the old-money families, slapping tacky art on the walls, serving badly cooked, heavy meals, and overpopulating the house with servants. John Tyler has a library, not because he likes to read, but he just likes to be able to say to guests, "I'll see you in my library." We're made sure to know it's a sadly neglected room. May is a genuine old-money aristocrat, and realizes what a sham it all is, but also contributes to her own undoing by being feckless and passive and easily manipulated.

But...there's also some good feminist undercurrents, with May being denied simple self-determination and always at the mercy of the men around her. And elements of class warfare, as servants turn on her viciously the moment she's suspected of murder, and interpret everything in the absolutely worst way possible, but also in John and Richard's treatment of May, viewing her as a tool or a decoration or a valuable asset, resenting her breeding and class but at the same time wanting it for themselves, but never truly seeing her or knowing her as a human being.

It's also left open to conjecture; did she murder her husband? Shearing doesn't think so; it was either the poison already in John's system, or an honest attempt on her part to help him out by giving him a dose of arsenic. A sympathetic lawyer speculates that it couldn't have been murder; she had too much to lose by his death, and everything to gain from a legal separation.

Another thing that makes it riveting is that it's based on a real case, that of Florence Maybrick, accused of poisoning her husband in 1889.

The novel follows the Maybrick case rather closely, changing names and the location (the real case was in Liverpool), and some circumstances. In this case, the woman was most likely having an affair or two, but in both the novel and real life, the woman's reputed affair did much to prejudice the public and the judge against her...while the husband's philandering was not even an issue.

And Maybrick, like May, was probably innocent, but too much was stacked against her and she was railroaded into jail. Modern readers might also feel outrage at the proceedings: the judge was obviously violently prejudiced against her (and soon after the trial was committed to an asylum, where he died mad), evidence was poorly handled, new evidence arose that was ignored, and all sorts of things happened that should have led to an appeal and retrial, but it was never granted. In both the novel and reality, the woman was accused of trying to make poison from arsenic-laden flypapers, but it was common for women to use that in skin treatments.

Florence Maybrick, born in Mobile, AL, spent 14 years in prison, and when she was released, returned to the US. She wrote a book about her experiences, but it didn't sell, and an attempt at a lecture career also failed. She eventually became a recluse, dying in a squalid cabin in Gaylordsville, CT, in 1941, at the age of 79. Two years later, Shearing's book came out, and in 1947 it was filmed as THE MARK OF CAIN with Eric Portman and Sally Gray, and with a script co-written by stellar mystery author Christianna Brand.

I read this as an interlibrary loan book; it's out of print but there's copies to be had here and there; I've found some listed on the aether listed for $5 or so. It's worth seeking out, and while it may seem slow-paced, it's got the slow buildup that modern readers don't appreciate.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Tales of the Shadowmen: The Modern Babylon

This is another case of "Great cover!"

The first in a series of anthologies from the good folks of Black Coat Press, these are different because they feature primarily characters from French pulp fiction, mingling with some other creations. For instance, the cover depicts a confrontation between Feuillade's Judex and Mary Shelley's Creature.

The stories are not merely "new adventures" of popular characters, but crossovers. Unfortunately, there's a few stories in here that function only as opportunities for characters to meet; however, at their best, the stories have a narrative that brings them together organically.

The cover illustrates "The Mask of the Monster" by Matthew Baugh, a decent story about the Creature surviving into early 20th-century France (and it's not bad for being his first work of fiction). Bill Cunningham's "Cadavre Exquis" suffers not only from trying to cram too much into a short story, but also from a bleak outlook as the heroic Fascinax's efforts turn out to be futile. And veteran TV writer, producer, and novelist Terrance Dicks of Dr. Who fame, gives one of the most unsatisfactory stories in the bunch, "When Lemmy Met Jules", which basically is only a meeting between Lemmy Caution and Jules Maigret, with minimal plot. Yawn.

Up next was Winn Scott Eckert's "The Vanishing Devil," which featured Doc Ardan, Jules Maigret, and Sherlock Holmes, and was pleasant enough but not overly memorable. Viviane Etrivert's "The Three Jewish Horsemen" is a delightful romp with Arsene Lupin and the Phantom of the Opera. And I really liked G. L. Gick's "The Werewolf of Rutherford Grange," largely because it's being serialized and can afford to take its time. It had good atmosphere and was more focused on story rather than throwing together as many characters as possible...which is a problem with Rick Lai's story "The Last Vendetta," which I felt was simply overpopulated with various characters and the dialogue existed mainly so people could drop pop-culture references.

Belgian author Alain le Bussy contributed the brief but very fun "The Sainte-Genevieve Caper" that has a meeting between Arsene Lupin and Sherlock Holmes (who crossed swords several times in Maurice Leblanc's original Lupin novels). Jean-Marc and Randy L'Officier (who edited this collection, by the way) contribute the amusingly Lovecraftian "Journey to the Centre of Chaos." "Lacunal Visions" by Samuel T. Payne is an adventure of Poe's C. Auguste Dupin, against a villain who seems to be a distant relative of Dr. Who. And Dupin shows up again in John Peel's "The Kind-Hearted Torturer," only this time having him connect with the Count of Monte Cristo.

"Penumbra," by Chris Roberson, was a lot of fun for me to read, as it not only crosses Louis Feuillade's two creations, Judex and Les Vampires, but also throws in Kent Allard, aka "The Shadow" of pulp classics, for good measure. "The Paris-Ganymede Clock" was an interesting bit of steampunk from veteran sci-fi scribe Robert Sheckley. And the collection is rounded up by Brian Stableford's mini-epic "The Titan Unwrecked; or Futility Revisited," which mixes fictional characters with real-life writers and millionaires on a luxury ship cruising across the Atlantic.

Is it worth reading? Oh hell yeah. Despite a few missteps, it's still a fun way of introducing yourself to some lesser-known characters, and there's fun and adventure to spare. The best pieces are actual STORIES, not merely literary contrivances, and for savvy readers, there's often a smile or a chuckle to be had.

This is the first in a series from Black Coat, and while there's room for improvement, the level of quality is still very high. Not quite required reading, but damn close.

The Phantom Ball...ushering in December

I decided to rename my "Musical Interlude" posts to something a bit more vivid...so for this orchestral piece, it's after my pipe-dream dance party, the Phantom Ball.

Outside, it's a cold, blustery night, the face of the moon occasionally passing behind wind-torn clouds. The ballroom of the old house is hung with mouldering hangings and festooned with cobwebs. The candelabras have gone unused for decades. But a strange bluish light shines from them, as the music starts from unseen hands. Soon the room is full of waltzing couples; a former owner dances with his wife, who poisoned him. Another dances with his mistress. A butler and a maid dance among them; in death, all are equal. Two men waltz together; a century ago they died in a strange suicide pact. Some couples are dancing as a punishment, being confronted with the sins they committed while alive; others are united in death with those they couldn't be with in life.

And when it's over, the dust on the floor is undisturbed, and the mortal observers, peeking in the door or through the window, aren't sure if it was real, or their imaginations.

Outside, it's a cold, blustery night, the face of the moon occasionally passing behind wind-torn clouds. The ballroom of the old house is hung with mouldering hangings and festooned with cobwebs. The candelabras have gone unused for decades. But a strange bluish light shines from them, as the music starts from unseen hands. Soon the room is full of waltzing couples; a former owner dances with his wife, who poisoned him. Another dances with his mistress. A butler and a maid dance among them; in death, all are equal. Two men waltz together; a century ago they died in a strange suicide pact. Some couples are dancing as a punishment, being confronted with the sins they committed while alive; others are united in death with those they couldn't be with in life.

And when it's over, the dust on the floor is undisturbed, and the mortal observers, peeking in the door or through the window, aren't sure if it was real, or their imaginations.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)