I've written about her a bit before, but here goes again. Elizabeth Canning (1734-1773) was a British servant girl who on 1/1/1753, disappeared while on a visit to some relatives, and showed up at her mother's home several weeks later, claiming to have been held prisoner in a spare room in a house outside London.

Bet Canning, as she was known, was a plain yet charming and shy girl, popular in her neighborhood. She was of the servant class, and worked for a year and a half for a Mr. Wintlebury, who ran a local tavern, then going to work for a local elderly man. She was a retiring sort and also very defensive of her virtue and reputation. Her given reason for quitting Wintlebury's was fear of defending her chastity from his customers. She was also what we today would call a survivor of a Traumatic Brain Injury; when young, the garret ceiling had collapsed on her head, leaving her prone to fits when surprised, spoken sharply to, or when hit on the head.

The case became a nine days' wonder. Canning claimed that she had been abducted on the street, then taken to the house where they had offered her a chance to become a prostitute. She refused, so they threw her in a narrow spare room where she claimed to have subsisted on crusts of bread and water for three weeks, until one day they didn't give her bread, at which point she ate a mince pie kept in a pocket since New Year's Day, and then the next day she found a boarded-over window could be penetrated, so she tore off the board, climbed out, and made her way back to London, a walk of ten miles.

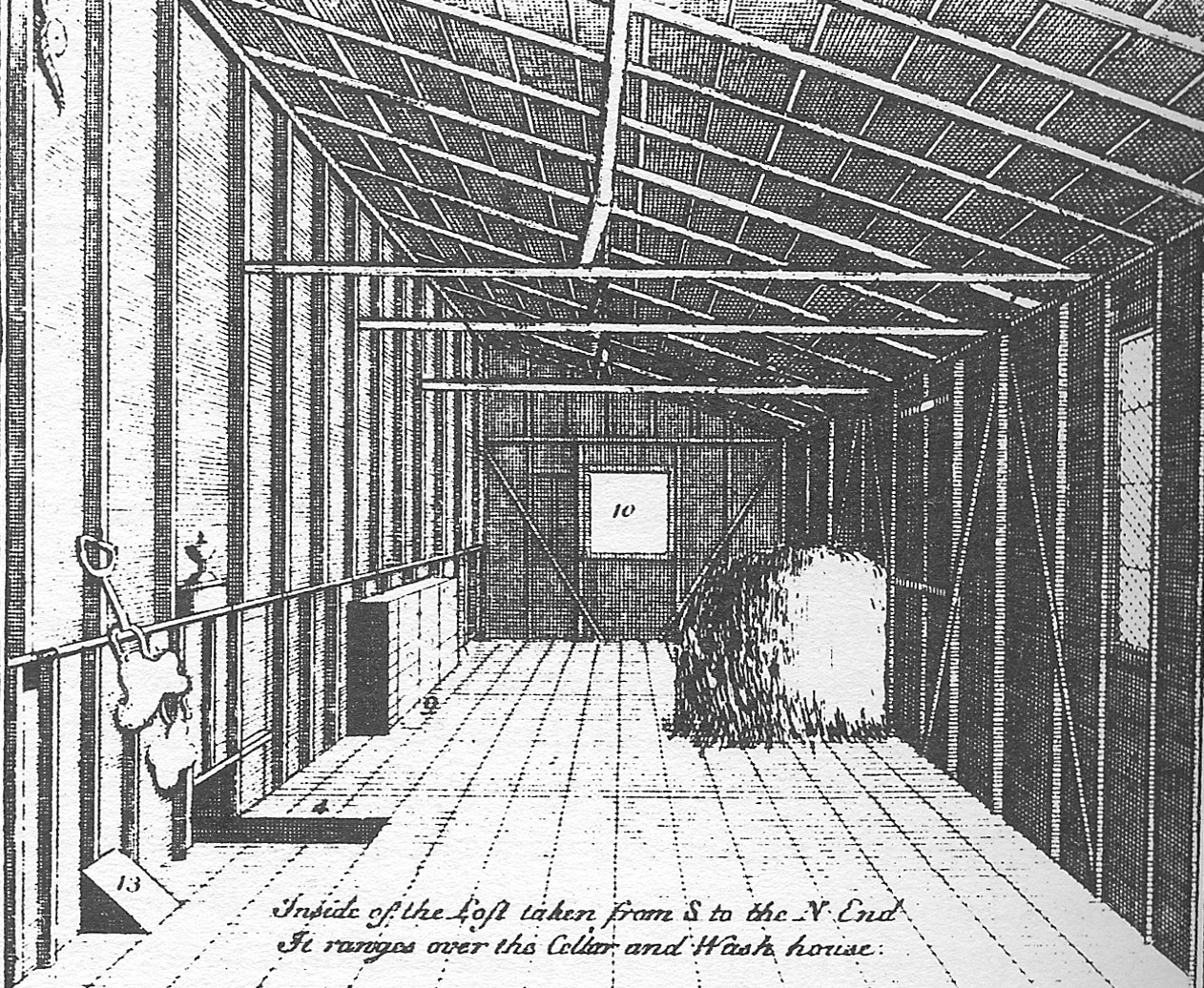

|

| A sketch of the room where Canning had claimed to be held. |

Canning was able to identify various objects around the house, but did not seem completely familiar with the room. There were no footprints found outside the window she had claimed to jump out of, but boards on the window showed to have been only recently nailed up. She claimed to recognize several people there, including a Gypsy woman named Mary Squires, a revoltingly ugly creature, who became a pivotal figure in the case, as it was she whom Canning claimed had stolen her clothing.

|

| Mary Squires |

The rest is history. Virtue Hall, an inhabitant of the house, claimed that Canning had indeed been brought by force to the house and corroborated Canning's statements. Based on hers and other testimony, Wells was found guilty, branded on the thumb, and was to spend 6 months in prison. Squires was sentenced to hang (for the theft of Canning's stays, of all things).

However...

There was lots of doubt over Canning's story. This was the age of broadsides and pamphlets hawked on streetcorners, that had stuff that would be considered libelous today. (In the modern age, that role has been taken up by blogs and comment threads on the 'net.) Accusations rang out here and there, claims running from Canning running off with a lover to Canning sneaking off to have an abortion to Canning and her family cooking up the story in order to reap donations. A number of officials, including trial judge Sir Crisp Gascoyne, felt Canning's story was improbable and launched their own investigation, which resulted in damning evidence that Squires had been nowhere near the house at the time Canning claimed to have seen her. Wells and Squires were exonerated, and Canning was tried, and found guilty of perjury. She was transported to the American colonies, where she lived out her days in Wethersfield, CT, where she died. (Does anyone know where her grave is? I'd love to see a picture.)

What happened? Theories abound. According to the facts I've dug up from several places, it looks like Canning was indeed abducted. Several witnesses did back up her story of being dragged off by two men; they had seen her been half carried, half dragged up to Enfield Wash. Canning was again seen after her escape, by a man of whom she asked the way to London. She had cut her ear while climbing from the window, and blood was found on the window frame. Sure, there were no footprints on the ground underneath the window, but there had been heavy rain the night after Canning's escape, so naturally they were washed away. Her physical condition upon returning home was well-documented by reliable sources and completely in sync with someone held prisoner for nearly a month.

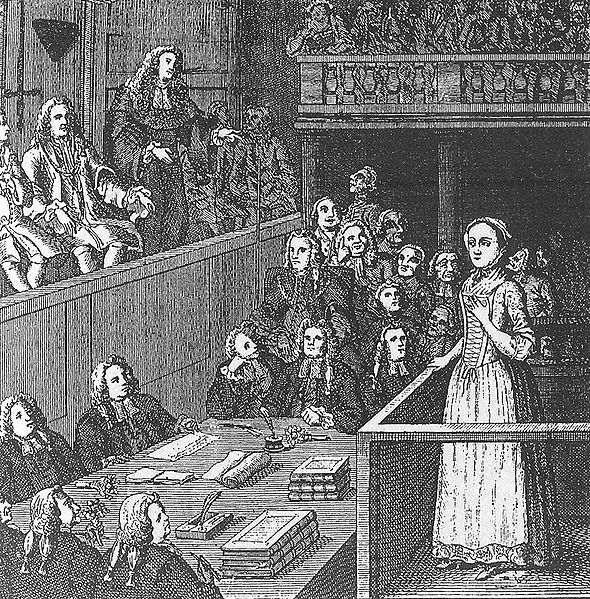

|

| Canning in the dock. |

But at the same time, there's so much of the story that doesn't click. Trying to torture a girl into prostitution? No way; a bawd of the age would simply have the girl raped and forced her to "work." Survive for three weeks on crusts of bread? How on earth did she have the strength to break out of her prison and walk to London? And with all the brothels in London, why carry a girl away to a bawdy house outside the city?

One overlooked aspect of the case was Bet's brain problems and fits. Andrew Lang, in an essay on her case, was completely sympathetic to her, but points out that her head injury could have messed with her perceptions of what happened. (He cites a case of a woman who slipped on ice, suffered a concussion and dragged herself to a shed where she later claimed to have been held prisoner, although she never was.) I finally got my hands on Lillian de la Torre's nonfiction overview of the case, Elizabeth is Missing, and she puts forward what seems to me to be the likeliest theory.

According to de la Torre, Canning wasn't telling the truth, but thought she was. What had happened clicks with the notion that Canning had actually been purposefully abducted and brought to that house on the behest of some man, likely Wintlebury, in the hopes that he could keep her there as his mistress. On the first night, he raped Canning. And what with Canning's phobia of sex and her obsession with her virginity, not to mention her fragile mental health, led to her going into a automaton-like fugue state. Her rapist quickly tired of her and turned her over to Wells, who found herself unable to get rid of the strange, bedeviled creature.

And then suddenly, one morning, Canning wakes in the spare room. She doesn't remember anything past New Year's Day, immediately assumes she's been kidnapped by white slavers, sees the sinister group through a hole in the floor, and immediately makes an escape. When asked her whereabouts, she quickly made up a story based on her assumptions (which I've heard happens with those with amnesia) and after time began to believe her story. Human memory is astonishingly malleable; if you read up on experiments by psychologists and neurologists, it is almost shockingly easy to create false memories in someone, even in yourself. And debate rages over the value of eyewitness testimony. A 1999 experiment had subjects watching a video of people playing basketball and counting the number of times people in white shirts successfully passed the ball; over half the subjects never noticed the man in the gorilla suit who walked onscreen, thumped his chest, and walked off. (I was at a live demonstration of it once; most of us knew about it, but several who weren't familiar with it did indeed miss the gorilla.) Once, as an experiment on myself, I changed a few details in a story I told and repeated often, and became alarmed in less than a month when I started to have trouble remembering what had really happened. It's scary.

|

| A scurrilous cartoon lampooning the Canning affair. |

Wells and Squire couldn't tell the truth; they had too much to lose, and either way they'd be prosecuted. By covering up for the rapist, they at least could keep his money, and potentially squeeze him for more. Virtue Hall probably tried to tell the true story, but was dismissed by Canningites, and later told what they wanted to hear...before finally recanting. It all clicks.

A sad part of her story is that Canning did commit perjury, although unwittingly. She didn't tell the true story. She couldn't. She couldn't remember what really happened.

Canning's story inspired a number of novels and stories, including The Franchise Affair by Josephine Tey and The Price of Murder by Bruce Alexander. And the details of this messy case are something to be remembered today.

| |

| Don't ask me, I don't know. |

-British-Library-Board.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment