Reeve's detective Craig Kennedy repeats his usual pattern of being hired to look into some crime, then using what was then high-tech equipment to foil the evildoers.

The first story, "The Poisoned Pen," is a tale involving a seemingly accidental poisoning of a young actress in a New England artists' colony. In fact, when I first read it I thought maybe Reeve had based the story on the real-life death of silent film actress Olive Thomas, who died in Paris of an accidental poisoning, but Reeve's story prefigures the Thomas case by nine years. Yikes! It's solved through skilled chemical analysis.

In "The Yeggman," (an old word for a burglar; sounds almost comical these days, doesn't it?), Kennedy is hired by an insurance company to look into a case of stolen pearls, and a maid chloroformed to death. He analyzes how the safecrackers worked, using low-level explosives, and lays a trap with a high-speed camera while going undercover in a gang of housebreakers. It's all lurid silent-movie stuff, like something out of Feuillade.

"The Germ of Death" is interesting in its sympathies for Russian revolutionaries in the days before the Red Scare, which really took hold in 1919. Kennedy investigates suspicious deaths in a cell of Bolsheviks headquartered in New York, which turns out to be done by a Czarist spy using typhus germs in an early case of bioterrorism. There's also an early appearance of a bomb-transporting device. It's kind of funny seeing Russian revolutionaries being depicted as so noble and idealistic, and the czarists so evil, when in a few short years there would be all sorts of sympathy for the czarists and the Bolsheviks would be so reviled. America is so fickle.

"The Firebug" has Kennedy hired to look into a rash of arsons, but all are around a chain of department stores. He solves the case with handwriting analysis (the arsonist conveniently sends taunting notes to the fire chief), legwork, and a "telautograph," a long-distance writer that allows him to summon a warrant. "The Confidence King" brings in the Secret Service as Kennedy deals with a counterfeit ring; we get a rundown of Bertillon's "portrait parle," and describes a bizarre method of changing one's fingerprints that is so loopy it just HAS to be bullshit, as I've never heard of it being done anywhere else. (My attempts to Google it have yielded nothing, so it's either something Reeve made up or else something that has since been discredited and discarded.)

| A telautograph. |

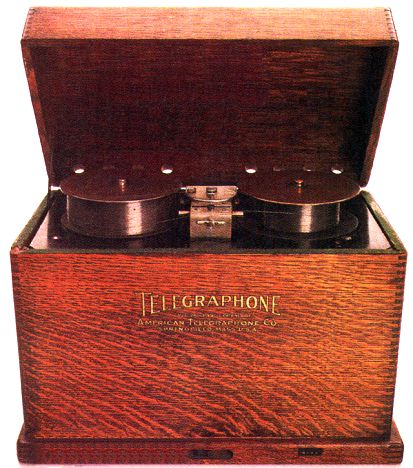

In "The Sand-Hog" Kennedy investigates evil deeds committed during the construction of a tunnel (sandhog is a term used for workers in excavation projects). Much is made of how the workers are operating in a pressurized environment, but the case is solved with a "telegraphone" or early bugging device.

|

| A telegraphone. |

"The Forger" has Kennedy up against a check-forgery scheme, which was seemingly easy to do back then. The case is resolved by judicious use of a "telectrograph," or early fax machine for sending photos. (It makes me want to dub the fax machine in my office the "telelectrograph," which would certainly bewilder most of my co-workers. My boss would probably join in, though.) "The Unofficial Spy" opens with a mysterious death in a hotel, segues into Kennedy explaining the so-called "endormeurs" of Paris (criminals who drug their victims then rob them, at least according to Reeve), and ends up with Kennedy improvising a bug and stumbling on a plot for freelance spies to sell vital documents. It actually goes to Washington DC, to "the house on Z Street" which doesn't exist. Reeve probably knew that.

"The Smuggler" has Kennedy brought in to foil an attempt to smuggle designer gowns and jewelry to high-fashion shops of New York, reminding me of Patricia Moyes' 60s novel Murder a la Mode that deal with industrial espionage in the fashion world. It's solved with the assistance of a photophone.

|

| A photophone. |

| A Draeger pulmotor |

Is it good? Not always; sometimes it's just too formulaic and clunky for its own good. But at the same time, it's kind of fun to read these stories that tackle criminal problems with "revolutionary" devices that are so quaintly interesting to us today. Sometimes the attitudes are eye-opening, like in its treatment of Bolsheviks. And from a steampunk perspective, it's a lot of fun. I almost want to experiment with some of these. But they're also fun from the perspective of putting yourself in a silent-movie frame of mind, which is how I read them. So if you're fond of that period, read away!

No comments:

Post a Comment