Never heard of Reeve? How about Craig Kennedy? No? Not surprising.

In the early part of the 20th century, Craig Kennedy was an enormously popular character, "the American Sherlock Holmes" as he was dubbed. Novels and short stories featured this fearless scientific detective. Movies were made about him. Why has the character dropped off the radar?

A good explanation may be that the Kennedy stories focused on science, and in our age the "groundbreaking" discoveries that were featured in the Kennedy stories are, well, mundane. Lie detectors? Seismographs? Oxyacetylene torches? Gasp!

There is a certain amount of fun in rediscovering these tales, though. The "amazing" technology used can be amusing, especially when Reeve and Kennedy are dealing with outmoded concepts and debunked theories. And the milieu (New York in the 1910s) is kinda fun, like peering into a silent movie.

THE SILENT BULLET was the first volume of Kennedy stories, published in 1912. A brief introduction makes us aware that the hero is Craig Kennedy, professor of chemistry at Columbia University, and his Watson is his journalist roommate, Walter Jameson. Although Kennedy is a chemist, he appears to be adept in all sorts of branches of science, as are revealed in the stories.

The first story is "The Silent Bullet," in which a supposed suicide in a brokerage firm turns out to be a murder committed with an exotic item, a silencer, and is solved by surreptitious use of that new invention, the lie detector. This story also has a terrible cringe-inducing line, toward the beginning, about how another murder was solved and proven to be committed by a black man, because a trace of blood from the scene tested similar to a gorilla's (apparently, caucasian blood reacts similar to a chimpanzee's). I'm willing to give Reeve the benefit of the doubt here, because he's quoting research from the Carnegie Institution...at least, I'm assuming it's genuine research, although Reeve could have been making it up off the cuff. But that's really the only slur in the book, so I'm thinking it was done out of ignorance rather than sheer racism. It's really a lot better than the racism that exudes from Lovecraft and Rohmer.

Next up is "The Scientific Cracksman," which gives us a wealthy man is found dead by an open safe, which was open, but no money taken. Who did it? How did he die? Kennedy uses an electric drill and a dynamometer (we're told he had permission to copy Bertillon's dynamometer), but ultimately the crime is solved psychologically, using a word-association test.

"The Bacteriological Detective" is next. A mysterious and suspicious case of typhoid shows up in the New York elite. The murder is solved through immunization records and handwriting analysis.

"The Deadly Tube" starts to get gothic, with its tale of a woman horribly disfigured, apparently through botched x-ray treatment for some blemishes. Kennedy suspects it wasn't an accident, and to clear the doctor discovers a hideous plan with the help of a hidden microphone. It's actually fairly up-to-date and uncomfortable, and has echoes of some other books I've read in recent years.

"The Seismograph Adventure" has a bit more gothicism; a wealthy man is throwing huge amounts of money at a spiritualist who is supposedly bringing him into contact with his late wife's spirit. As the title implies, it's solved via a seismograph that can differentiate between footsteps, before a murder can occur.

"The Diamond Maker" concerns itself with a murder and a spectacular diamond robbery. What could have burned a hole in the impregnable safe? Kennedy teaches us about the new chemical thermite (he calls it "thermit" but you know what it is); the criminals (including a faux-alchemist) end up being trapped by a crude solar cell.

"The Azure Ring" has echoes of the Holmes adventure "The Devil's Foot," with two people found dead in a locked room. There's a charcoal brazier in there, but the bodies show no sign of carbon monoxide poisoning. It turns out to have been committed with a poison new to western science, curare.

In "'Spontaneous Combustion'" a wealthy man burns to death, and the big question is over his will. Kennedy dismisses the spontaneous-human-combustion angle (a phenomenon still debated today) and uncovers the murderer with bloodspot analysis.

"The Terror in the Air" overflows with period atmosphere. A pilot friend of Kennedy is having trouble with his aeroplanes (that's what they called 'em!), especially when his new gyroscope device burns out mid-flight and causes a crash. Kennedy uncovers a villain using a Tesla-type broadcast energy device to burn out the gyroscopes!

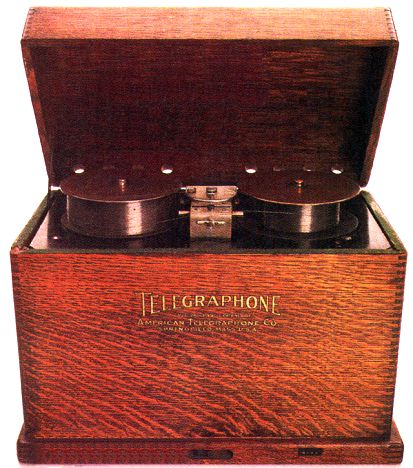

"The Black Hand" is an early story of the Mafia, in which Kennedy and Jameson come to the aid of an opera singer whose daughter has been kidnapped. Italian-Americans are treated with respect, and Kennedy closes the case using a dictograph.

"The Artificial Paradise" is a bit problematic. Kennedy has always been a law-and-order type, but this time he aids and abets a crime. He's called in to find a rubber manufacturer who has disappeared. It seems the man is part of the revolutionary junta in the South American country of "Vespuccia," and has been smuggling guns and ammunition from New York to his comrades. We're to understand that the revolution is a noble cause, but it's also stated that Kennedy invested money in Vespuccian rubber, and the revolution will benefit him monetarily. It's not something I was entirely comfortable with reading the story. It turns out the missing man was involved in a mescal-cult, and the end is totally over-the-top, when the missing man, supposedly dead of an overdose, is electrically resusitated!

"The Steel Door" is the final story, in which Craig aids a police raid of an illegal casino, protected by a thick steel door. There's a lot of great atmosphere in the club, and Kennedy not only bypasses the door with an oxyacetylene torch, but also uncovers the rigged games. It's also rather modern in its depiction of a casino regular who's addicted to gambling.

Reeve started off as a journalist, and his style is evident in the stories, which are straightforward in their storytelling. No flowery language here, just straight-ahead plot with little character development (if any). Reeves continued the series through the 20s, writing screenplays around Kennedy and also for Harry Houdini, until the film industry migrated to California and he preferred to stay in New York. He declared bankruptcy in 1928 after a film deal went sour, but re-emerged in 1930 as an anti-racket crusader, and Kennedy shifted from being a scientist to a gangbuster. Reeves died in 1936, at the age of 55. I've been unable to find anything about his personal life and I'd love to know.

I'll be reading more Reeve/Kennedy in the future, so stay tuned. If you want to read them yourself, it's easy. Much of Reeve's work has fallen into the public domain, and THE SILENT BULLET is available through

Project Gutenberg,

Manybooks, and

Munsey's, and probably a number of other sites, so go look around...